Stars appear to be exclusively white at first glance. But if we look carefully, we can notice a range of colors: blue, white, red, and even gold. In the winter constellation of Orion, a beautiful contrast is seen between the red Betelgeuse at Orion's "armpit" and the blue Bellatrix at the shoulder. What causes stars to exhibit different colors remained a mystery until two centuries ago, when Physicists gained enough understanding of the nature of light and the properties of matter at immensely high temperatures.

Specifically, it was the physics of blackbody radiation that enabled us to understand the variation of stellar colors. Shortly after blackbody radiation was understood, it was noticed that the spectra of stars look extremely similar to blackbody radiation curves of various temperatures, ranging from a few thousand Kelvin to ~50,000 Kelvin. The obvious conclusion is that stars are similar to blackbodies, and that the color variation of stars is a direct consequence of their surface temperatures.

Cool stars (i.e., Spectral Type K and M) radiate most of their energy in the red and infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum and thus appear red, while hot stars (i.e., Spectral Type O and B) emit mostly at blue and ultra-violet wavelengths, making them appear blue or white.

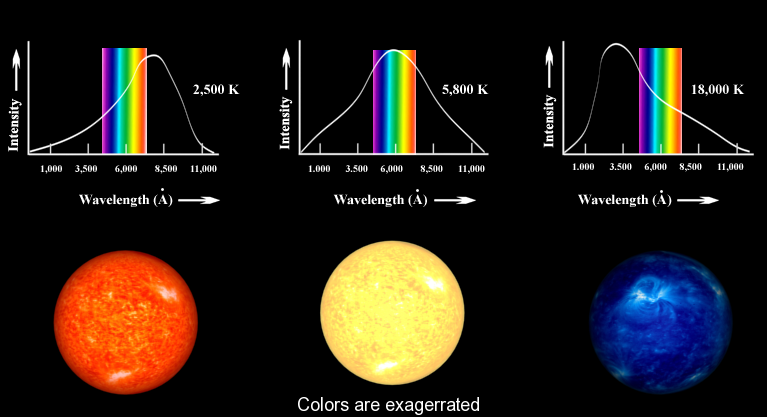

To estimate the surface temperature of a star, we can use the known relationship between the temperature of a blackbody, and the wavelength of light where its spectrum peaks. That is, as you increase the temperature of a blackbody, the peak of its spectrum moves to shorter (bluer) wavelengths of light. This is illustrated in Figure 1 where the intensity of three hypothetical stars is plotted against wavelength. The "rainbow" indicates the range of wavelengths that are visible to the human eye.

Figure 1

This simple method is conceptually correct, but it cannot be used to obtain stellar temperatures accurately, because stars are not perfect blackbodies. The presence of various elements in the star's atmosphere will cause certain wavelengths of light to be absorbed. Because these absorption lines are not uniformly distributed over the spectrum, they can skew the position of the spectral peak. Moreover, obtaining a usable spectrum of a star is a time-intensive process and is prohibitively inefficient for large samples of stars.

An alternative method utilizes photometry to measure the intensity of light passing through different filters. Each filter allows only a specific part of the spectrum of light to pass through while rejecting all others. A widely used photometric system is called the Johnson UBV system. It employs three bandpass filters: U ("Ultra-violet"), B ("Blue"), and V ("Visible"); each occupying different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The process of UBV photometry involves using light sensitive devices (such as film or CCD cameras) and aiming a telescope at a star to measure the intensity of light that passes through each of the filters individually. This procedure gives three apparent brightnesses or fluxes (amount of energy per cm2 per second) designated by Fu, Fb, and Fv. The ratio of fluxes Fu/Fb and Fb/Fv is a quantitative measure of the star's "color", and these ratios can be used to establish a temperature scale for stars. Generally speaking, the larger the Fu/Fb and Fb/Fv ratios of a star, the hotter its surface temperature.

For example, the star Bellatrix in Orion has Fb/Fv = 1.22, indicating that it is brighter through the B filter than through the V filter. furthermore, its Fu/Fb ratio is 2.22, so it is brightest through the U filter. This indicates that the star must be very hot indeed, since the position of its spectral peak must be somewhere in the range of the U filter, or at an even shorter wavelength. The surface temperature of Bellatrix (as determined from comparing its spectrum to detailed models that account for its absorption lines) is about 25,000 Kelvin.

We can repeat this analysis for the star Betelgeuse. Its Fb/Fv and Fu/Fb ratios are 0.15 and 0.18, respectively, so it is brightest in V and dimmest in U. So, the spectral peak of Betelgeuse must be somewhere in the range of the V filter, or at an even longer wavelength. The surface temperature of Betelgeuse is only 2,400 Kelvin.

Astronomers prefer to express star colors in terms of a difference in magnitudes, rather than a ratio of fluxes. Therefore, going back to blue Bellatrix we have a color index equal to

B - V = -2.5 log (Fb/Fv) = -2.5 log (1.22) = -0.22,

Similarly, the color index for red Betelgeuse is

B - V = -2.5 log (Fb/Fv) = -2.5 log (0.18) = 1.85

The color indices, like the magnitude scale, run backward. Hot and blue stars have smaller and negative values of B-V than the cooler and redder stars.

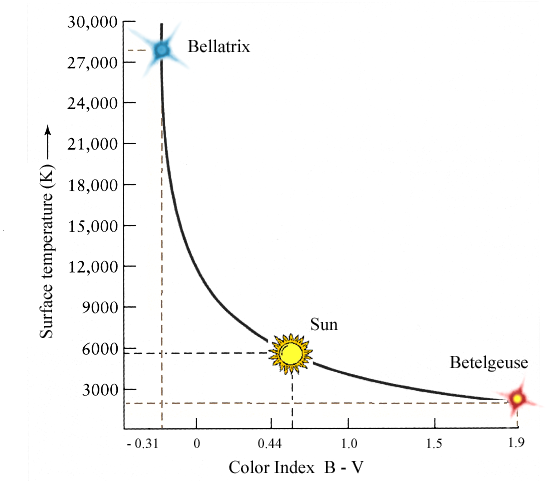

An Astronomer can then use the color indices for a star, after correcting for reddening and interstellar extinction, to obtain an accurate temperature of that star. The relationship between B-V and temperature is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

The Sun with surface temperature of 5,800 K has a B-V index of 0.62.